So I made a thing. You can play it here, and the code is here.

You might be thinking “ok, so it’s a blog post on writing a retro game of breakout”, but nope - I didn’t even write the game code. And that’s kind of the point of this post. Come see how many turtles are on each others’ backs.

TL;DR - Advent of code-code, in a Rust interpreter, in a WebAssembly module, in a browser, works really very well. But not all browsers are created equally when it comes to WebAssembly. And we have a little look at tooling to profile your WebAssembly.

So where is the code from?

I love advent of code, you get a coding challenge each day in December, and it starts quite simple, but ratchets up as the days go on, to really challenging and gives that feeling of satisfaction when you solve each day. Until you look at the scoreboard to find out someone solved it in 0.71 seconds.

But why I really love it is that it’s a great context to try out a new language, or one you want to get to grips with more, for example last year I did the advent of code in Haskell. By the end of it my Haskell was much improved, albeit from a pretty poor base! And then I got thinking - I want to learn Rust - why not do one of the previous years of advent of code (they’re all there online still - again, it’s a great resource), so I did!

Rust

Rust is a brilliant, performant, small-footprint, memory-safe language that excels in situations with limited memory, embedded systems, or where low-level optimizations or high security are needed. It’s a bit like a spiritual successor to C, it terms of low-level-ness, but with modern niceties like lambda functions, a trait system, and did I mention memory-safe? I once wrote so C code with what I thought was some pretty clever pointer arithmetic in it… that then took a university of Nottingham linux box completely out due to a pernicious out-of-bound error. With rust - the program never would have compiled.

So off I went with rust, and the the first few tasks were like a stroll through a meadow - Rust has a lovely type system, good ecosystem, and a cute little mascot, it was a joy to program in. Then I met the borrow checker. For those that don’t know Rust’s learning curve faintly resembles:

I hit the borrow checker, and I hit it hard. The borrow checker is the thing in rust that guarantees you don’t access memory you can’t/shouldn’t. And it turned out writing your own graph structures in Rust is known to be a tricky problem due to how memory ownership works, especially mutable graphs. I didn’t know this and happened to stumble into it, found it really hard, so took the only logical path: gave up for 6 months!

Anyway, several months later I stumbled across this link, and took heart from the fact that I had hit something which is harder in rust than other languages, and solved the task by switching to a tree structure. (FYI - I now know that several good libraries exist for dealing with graphs in rust… use them!)

Several of the tasks build together to have you make a custom code interpretor - and in a lisp like manner the code can manipulate itself, e.g. all commands are integers and command outputs can be written to other code locations, to be later read as commands that can, etc… It’s a cool set of problems that builds into a generic turin-complete language with relatively few commands and modes, I recommend giving the 2019 advent of code a try if that sounds interesting to you.

Breakout

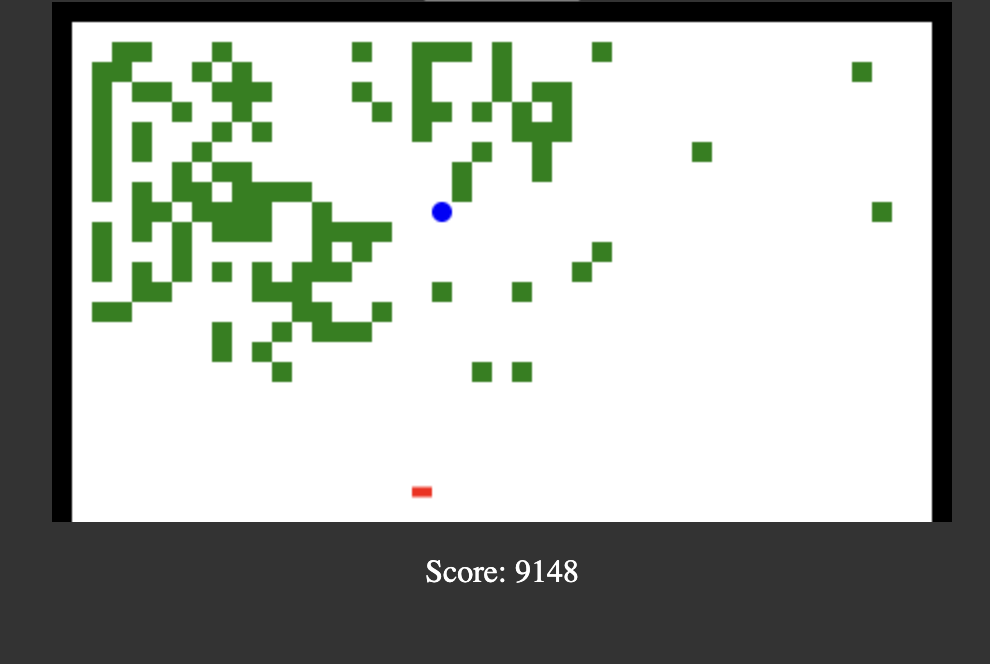

So, spoiler warning, day 13 gives you the code for a breakout game, but you have to wire in a display and controls, as well as having your interpreter running the actual code. I made a very basic ASCII interface outputting to the terminal for the first version but then thought - wait, rust leads itself very nicely to WebAssembly (WASM), why don’t I try bundling it up then using good old HTML, CSS and JS to do the controls and display?

So it turns out the good people at the “Rust and WebAssembly working group” have made a really powerful starting template: rust-webpack-template. If you take nothing else from this post, bookmark that link. Like, right now. As in stop reading this and bookmark that link. Done? Good, then let’s carry on.

A dollop of <canvas>; a smidgen of JS; and because I believe we’re losing the ability to disagree well, there’s even a light colour scheme if you have your system preference is set to light - I’ve got your back, even if your choices are an anathema to me…

And the result is a very playable game. Or rather it’s actually quite challenging on your reflexes and I’m partially sighted, so I cheated and wrote a small bit of code to play the game for me!

Not all browsers are created equally

But this is where things get interesting. I noticed the game initialized markedly faster on some browsers. Turns out WASM speed varies widely across browsers. So I let rust’s wasm-pack build an optimized version (of the unoptimized rust code) and took some measurements:

| Browser | Run Time |

|---|---|

| Chrome | 18.9s |

| Firefox | 4.6s |

| Safari | 3.6s |

| Chrome (android) | 319.5s |

| Firefox (android) | 14.6s |

Table 1: Running the base code with no UI component with no input until the game ends, and it does that 10 times in a row for total time.

So Chrome is lagging a bit on this metric, but WebAssembly is still experimental and even by the time you read this post the ordering may have completely changed as browsers improve. But since chrome on android is really quite slow, that gives us an opportunity to look at the code and start to optimise.

How do you even optimize web assembly code?!

I deliberately haven’t posted any code up to this point, as the code was hacked together quickly, cramped into a web assembly container, and that was badly wired into the browser. However, in my experience that’s how a lot of good bits of code start: with the question of ‘I wonder if?’, then proof-of-concept, then to this point of: ok, this code shows enough merit to put more time into, where do we even start?

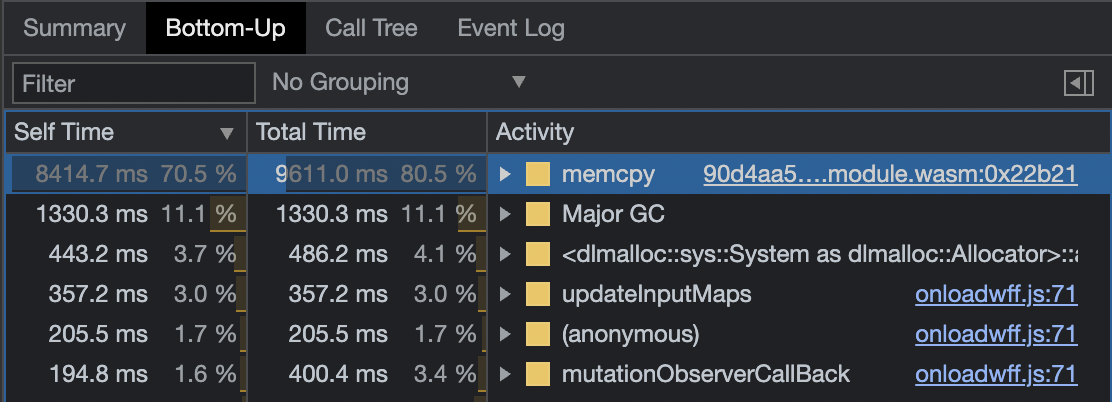

Whilst I normally just plough into fixing what I think will be slow in the code (a case of do as I say, not as I do), let’s have a look at what timings we can easily get access to. Luckily for us, if we build with name symbols (as easy as npm start over npm run build in the rust-webpack-template), then the browser’s own profile can tell us a lot:

Here we see we’re spending most of our time in memcpy in Chrome, and a bit in major garbage collection, probably due to all the memory needing to be freed. So why are we copying so much? Looking at the code gives us a good idea.

Clone, clone everywhere, but not a self to mutate

So you might ask what does each step of the program look like? Well here’s the start of it:

pub fn step(&self, input: i32) -> Self {

let mut clone = self.clone();

clone.input = input as i64;

let (x_state, x_opt) = run_to_next_output(&clone);

if let Some(x) = x_opt {

//...

What’s that first line you ask? Here self is the entire State type for the game, containing the current game code itself, and anything else to represent the current state of the program. And yes, we’re copying intcode-and-all into a new variable, and the program does this at other points as well. Why? Well whenever I approach an Advent of Code problem where I need to deal with state in some way I use a Haskell-like pattern - never manipulate the inputs given, copy and change-on-copy if needed. So the functions look broadly like f(old_state) -> (new_state, additional_outputs). Haskell loves this pattern so much they made a Monad for it.

This is a really powerful pattern, for example in a sudoku solver: a few basic rules can get you pretty far then if you get to a place you can’t move forward from, then if you use this fully pure model then you can just fill in a random square and then see if you can then reach a solution, and if you can’t you can unwind your state to where you made that choice and go another route. If you change a single state object as you go, you can’t really undo. So this pattern leaves open a lot of doors. But is it performant? Hell no; although credit where credit’s due, Haskell’s lazy-evaluation does do a lot to try to make it not un-performant. But we’re dealing with rust here, and .clone does what it says on the tin.

So what would happen if we said - stuff that, let’s mutate the state we’re given rather than copying the state everywhere? Well that’s coded up as MutState in the src/lib.rs in the source. and it’s fair to say it’s a little faster:

| Browser | Run Time |

|---|---|

| Chrome | 76ms |

| Firefox | 63ms |

| Safari | 70ms |

| Chrome (android) | 359ms |

| Firefox (android) | 159ms |

Super performant, over 50x faster, and even chrome on android is now over an order of magnitude faster than the previous champion - desktop safari with unoptimised code.

Conclusions

So WebAssembly, whilst still experimental, can give extremely good performance; there is half-decent tooling around it which is improving everyday (one more shout out to rust-webpack-template!); and it can allow you to combine the best of the web with the best of your favourite non-web language. Here it was Rust, which continues to impress, but personally go is my goto language (yes - a ‘go’ and ‘goto’ pun in one - I know - amazing.) so I will be looking for opportunities to combine go and the web through WebAssembly in the future.

And if you’ve read this far, thanks for taking the time. - Phil